Critical essays

'…there's no such thing as a grown up person' (Andre Malraux, Anti–Memoirs, 1968)

Deft and light of touch, we can easily imagine the sound of the artist's sharpened pencil tip on a soft sheet of buttery-cream cartridge paper. There is rhythm here, gentle caresses and quick-witted lines for us to enjoy. Without the distraction of colour, tone and form take shape; a button, a heel on a shoe; a soft, wolf-grey wisp of a girl; a few men in solid, armour-like suits mingle amongst 'the women'. But there is also a suit-wearing woman here. Separated from the herd, her back turned, she looks at a painting of uncertain content alone. The others, exhibitionists and voyeurs – who have come to be looked at as much as to look – have made an exhibition of themselves. And here they are cut down to size, a picture at an exhibition.

Deft and light of touch, we can easily imagine the sound of the artist's sharpened pencil tip on a soft sheet of buttery-cream cartridge paper. There is rhythm here, gentle caresses and quick-witted lines for us to enjoy. Without the distraction of colour, tone and form take shape; a button, a heel on a shoe; a soft, wolf-grey wisp of a girl; a few men in solid, armour-like suits mingle amongst 'the women'. But there is also a suit-wearing woman here. Separated from the herd, her back turned, she looks at a painting of uncertain content alone. The others, exhibitionists and voyeurs – who have come to be looked at as much as to look – have made an exhibition of themselves. And here they are cut down to size, a picture at an exhibition.

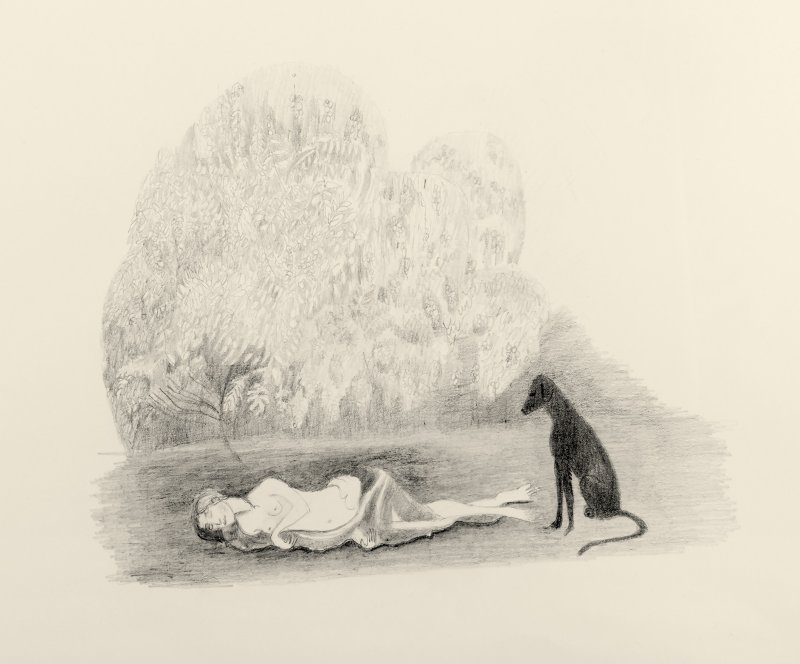

These drawings are like tiny jewels, love letters and party invitations from the artist to join a miniature and minutely observed world of magical, doll-like figures or circus animals (where pigs do indeed fly). It is a world of fun. And yet, as in all fairy tales, there is a dark side too. There is a sense that the crocodiles are not far behind us – or perhaps ahead of us, or even dangerously beneath our feet. They are, in fact, everywhere lying in wait to snap at our ankles. Chop-chop, and the feet are gone. As in Hans Andersen's magnificent tale The Red Shoes (and oh! the shoes, the fabulous shoes in Roper's drawings – to say nothing of the frocks and fabrics) we must all perform and make something of our lives until the final curtain drops. But whether sooner, or later, we all fall down. Once upon a time will inevitably become The End. In the meantime for Roper the angel is in her love of detail. The drawings are wistful, and mischievous too, as if something of the artist as a small girl remains.

The child of course lives in a rich tapestry where fantasy and reality are intricately interwoven – and where fantasy still has the power to trump reality. This is a world of play, and it is this imaginative world that artists also inhabit. In Roper's work such a world is only a hop, skip and a jump away and both restlessness and calm haunts the larger paintings. There is a sense here of figures that on the move, somewhere between where they have come from, or are going to, neither children nor quite adults. While we cannot go back, neither can we ever fully go forward. Grown women are stuffed under tables. They may be playing (or then again, maybe not). These scenes are often of domestic interiors, ambiguous places of both warm, and sometimes cold, comfort. In Roper's dreamlike painting washes of cobalt and ultramarine blues, verdant and leafy greens, toffee apple reds, gamboge and cadmium yellows – an entire liturgy of sensuous colour – beckons, inviting us into a luminous and enchanted world somewhere between reality and fantasy. There are chequered floors (and lives), and outside there are seas and rivers and boats of escape that carry the lovers – but to where? In the game of hide and seek it is never really clear who is hiding and who is seeking. The subjects are to all intents and purposes lost to each other. One can imagine a commandment: Hide and ye shall seek; Seek and ye shall hide. We remain mysteries not only to others, but also to ourselves. Hide as much as you want and you will be found out. Seek all you want and there will still be something hidden.

Psychoanalysis teaches us that the unconscious changes very little over time and therefore largely remains the repository of infantile wishes and desires (hence the priest's conclusion in Malraux's Anti–Memoirs). These are simple things, the very stuff of life, where murderous intent co-exists with a love supreme: I HATE you; I want to kill you or I LOVE you; I could eat you up. There is something here of the Garden of Eden after the Fall, especially in the paintings, with their reflective mirrors and figures covering their eyes so that they may not directly see the naked truth (or the Gorgon's stare?). But of course just like the child we must look, in spite of everything we know as adults, and every single day to be in the world means risking being expelled or devoured – part or whole. Roper reminds us that after all the shenanigans, the fun, the games, the bread and circuses of life with its pleasures and its pains, we are human. And of course this also means there is indeed no such thing as a grown-up person.

Dr Roberta Wilson McGrath, Reader in Photographic History, Theory and Criticism, School of Arts and Creative Industries, Edinburgh Napier University

In the Exhibition Catalogue for ‘Fable and Fantasy’ (six realists of the unreal, Adrienne Craddock, Elisabeth Frink, Karolina Larusdottir, Ana Maria Pacheco, Paula Rego and Gerda Roper) Peter Suchin, Critic in Residence for the 1996 Year of the Visual Arts wrote the following excerpts:

“The work of the artists collected together here ultimately coheres as a series of approaches to what one might term ‘unreal realism’, a selection of ways of picturing the world from the points of view of the fabulous, the mythical, the near-surreal or fantastic.

“The work of the artists collected together here ultimately coheres as a series of approaches to what one might term ‘unreal realism’, a selection of ways of picturing the world from the points of view of the fabulous, the mythical, the near-surreal or fantastic.

“It is not my intention here to reduce such a diversity to a few formulaic traits, restricting what is plural to a few neat strategies of artistic practice. I propose, rather, to give some suggestions – and they are only that – as to how the numerous works in this display might be productively read.

“Sometimes a pretty, sleek or sweet surface can deceive. Gerda Roper’s muted colours and dissolving compositions are palimpsests of deception in ways that only a close inspection might uncover. Scintillating splashes and patches of paint that may at first glance appear to develop into pleasant reveries, seeming daydreams, are in fact the medium in which an altogether darker reflexive texture is held. Titles act as clues to guide the viewer towards these deeper themes. These works operate at the fringe of the figurative. Mallarme’s remark that one should ‘paint not the thing but the effect it produces’ comes to mind.”

Peter Suchin, Critic in Residence for the 1996 Year of the Visual Arts

“What sticks in my memory about your drawings is that they were like delicate vignettes. Reflections, remembrances – fleeting, tiny (literally) and delicate. Intricate but fragile. Almost as if you breathed on them they would blow away.

“I loved the fact that they were so effortlessly wrought at times – the rubbings out and the painstakingly fine, delicate detail – and at others clearly spontaneous. The figures appearing to be placed so randomly, off-kilter on the big sheets. Demanding that you look closer, closely at them. Details, part of a bigger picture, perhaps?

“I loved the fact that they were so effortlessly wrought at times – the rubbings out and the painstakingly fine, delicate detail – and at others clearly spontaneous. The figures appearing to be placed so randomly, off-kilter on the big sheets. Demanding that you look closer, closely at them. Details, part of a bigger picture, perhaps?

“I remember the figures were sometimes twisted and bent like ballet dancers – fine and posed. Others awkward and ill at ease. Most were happy, at peace.

“These were the pleasures of life, small and everyday – and yet important memories, the very stuff of life itself, that we keep carrying around everyday in our heads. Your art exists there now too.

“I thought they were really lovely.”

Howard Burch, Head of Drama, Keshet International (also producer of TV drama series including Loaded, Hustle, Spooks, Ashes to Ashes, Moving Wallpaper, Echo Beach)

To encounter is to come upon or meet with something unexpected, and so encounters are at the heart of viewing a work by Gerda Roper. Often autobiographical and always universal, Roper's images explore realities of the female experience – domestic, psychological, imaginative, sensual and maternal.

Roper constructs narratives of being woman; of mother, of lover, of friend, interested observer, or of family situations. These narratives are often fragmentary, glimpses of moments held in time, encounters set in shifting spaces and perceptions.

The works are carefully wrought and crafted. They are poetic, intricate, decorative, domestic in scale, subject and content, and they utilise whimsy and humour as a subtle guide into other worlds and experiences. They bring together internal and external realities, dreams and fantasies, the observed and the imagined.

Gerda Roper's recent work includes a series of drawings and paintings entitled Hide and Seek. Made over a period of thirty years these paintings emerged from drawings about children's games. Roper describes, "the enduring thrill of playing Hide and Seek. I played it as a child in large houses in the dark, I played it with my child and I see it is still being played with the same fearful abandon". She remembers that her son used to hide and close his eyes, and say "I am not there", as if by not seeing he could not be seen.

The game of Hide and Seek has a long history and may have originated in the need for children to learn to develop skills of escape from enemies – to hide, or to seek for food or to seek out hidden enemies. Child psychologists emphasis the need for children to go out by themselves and explore, to gain autonomy and confidence in their independence, but remind us that no sooner have children felt the joy and thrill of exploration than they get lonely and seek reassurance. Therefore the child both hides and seeks. The finding and reuniting part of the game reassures the child that people in relationships can separate and yet come back together again, and the dance of separation and reunification indicates that separations can be temporary and are therefore safe. Recent research by Moll and Khalulyan (2016) considers the excitement of escaping someone's glance and thus making oneself invisible, as indicating an idea in the child's mind that 'I can see you only if you can see me' and thus unless two people make eye contact it is impossible for the one to see the other, because children insist on mutual eye contact for recognition.

One of the most powerful stories of Hide and Seek is The Lion, The Witch and The Wardrobe by C.S. Lewis, in which the Pevensie children are evacuated from London during the Second World War, to the country house of Professor Digory Kirke where the strict housekeeper Mrs Macready explains that he is unaccustomed to having children around him. During a game of Hide and Seek, Lucy, one of the children, hides in a wardrobe which opens up into the fantasy world of Narnia. Her experiences in Narnia enable her to overcome the trauma of being uprooted from her home amidst the bombing of London. Lucy's decision to hide in the wardrobe results in fantasy journeys and challenges involving seeking and reuniting.

In the painting by Gerda Roper entitled Hide and Seek, 1989, the boy child attempts to conceal himself beneath a red chair that is set under a glass table in the centre of which stands a vase of flowers. The adult female figure positioned in the top quarter of the painting is bent over looking for, rather than at, the child. The boy is looking away from the woman – who may or may not be his mother but certainly appears to be a relative, out towards the left of the image possibly towards someone else, or perhaps to a place beyond the viewer. The red chair is covered in rich patterned fabric and illuminates part of the boy beneath. The woman wears a yellow patterned dress which permeates into the patterned floor lighting the space between her and the child and linking them together. The floor and the internal spaces of the room appear liquid and water like, permeable and translucent like blue moonlight, but the painting is still and held in its own moment. Writing about this series Gerda Roper says, "in some of them I am trying to get that moment when you have to hold your breath, because breathing will give you away". She also recalls, "the sneaking back to base, the muffled sounds, and that the strangeness of objects in a half light and in the dark, make the negotiation of space perilous". In the painting, the viewer can see both figures and the woman can see the child. The child is alone and believes himself to be invisible because he is not in eye contact with the woman, however he may be seeing someone beyond the painting. The flowers in the vase look like white lilies possibly symbolising purity, commitment and rebirth, but the leaves cascade down over the side of the pot suggesting a more aquatic flora that points our eye towards the child beneath the table. The pot and the glass table together form a larger spherical shape that is beguiling but undefined suggesting that the child may be looking into a glass ball, to the future and away from the female figure.

In the painting by Gerda Roper entitled Hide and Seek, 1989, the boy child attempts to conceal himself beneath a red chair that is set under a glass table in the centre of which stands a vase of flowers. The adult female figure positioned in the top quarter of the painting is bent over looking for, rather than at, the child. The boy is looking away from the woman – who may or may not be his mother but certainly appears to be a relative, out towards the left of the image possibly towards someone else, or perhaps to a place beyond the viewer. The red chair is covered in rich patterned fabric and illuminates part of the boy beneath. The woman wears a yellow patterned dress which permeates into the patterned floor lighting the space between her and the child and linking them together. The floor and the internal spaces of the room appear liquid and water like, permeable and translucent like blue moonlight, but the painting is still and held in its own moment. Writing about this series Gerda Roper says, "in some of them I am trying to get that moment when you have to hold your breath, because breathing will give you away". She also recalls, "the sneaking back to base, the muffled sounds, and that the strangeness of objects in a half light and in the dark, make the negotiation of space perilous". In the painting, the viewer can see both figures and the woman can see the child. The child is alone and believes himself to be invisible because he is not in eye contact with the woman, however he may be seeing someone beyond the painting. The flowers in the vase look like white lilies possibly symbolising purity, commitment and rebirth, but the leaves cascade down over the side of the pot suggesting a more aquatic flora that points our eye towards the child beneath the table. The pot and the glass table together form a larger spherical shape that is beguiling but undefined suggesting that the child may be looking into a glass ball, to the future and away from the female figure.

In the painting Hide and Seek in the Quiet of the Day, 2020, a young girl with long hair in two plaits wearing a yellow dress with orange patterning appears to be crawling across a blue and white geometrically patterned floor in order to hide under a table. The table is deep ultramarine blue and circular, and is supported by a single central pedestal. On the table sits a pot with a houseplant in it. The left side, and about one fifth of the painting, depicts a curtain which is covered in a leaf format pattern in blues, yellows and oranges that echo and complement the other elements of floor, figure and table. The painting is lit from the back by a pinkish tinged plane that holds subtle traces of floral patterning. About four fifths of the painting is built of pattern; only the arms, legs and face of the child, the table and the plant pot are without decoration. The child is looking into the floor, and is simultaneously supported by, and held within, the blue and white pattern of the floor. The figure of the child is the central image of the painting, however, the narrative is emmeshed into the patterned depictions of the domestic interior. The stark way in which the curtain fabric section is placed against the patterned floor denies the suggested space of the room, compressing the depth of illusionistic space occupied by the child, and forcing the figure to sit more clearly at the front of the painting space. This pictorial device reveals rather than conceals the child, allowing that figure to be more vulnerable and less protected than the image initially suggests. Although at first glance this is a single figure painting, the viewer and potentially another person, child or adult, are behind the curtain. This absent presence provokes an underlying uncertainty about the nature of the game being played out, and the nature of the person behind the curtain. If the viewer is indeed the only one behind that curtain then there is an atmosphere of discomfort at the centre of that viewing. Gerda Roper has referred to the "dread of being found or worse, forgotten" that is an essential part of the game of Hide and Seek. In Hide and Seek in the quiet of the day there is a sense that the hidden person who is behind the curtain, beyond the painting, is observing but not necessarily seeking the child, and thus in this painting there exists the possibility of being seen but not sought.

In the painting Hide and Seek in the Quiet of the Day, 2020, a young girl with long hair in two plaits wearing a yellow dress with orange patterning appears to be crawling across a blue and white geometrically patterned floor in order to hide under a table. The table is deep ultramarine blue and circular, and is supported by a single central pedestal. On the table sits a pot with a houseplant in it. The left side, and about one fifth of the painting, depicts a curtain which is covered in a leaf format pattern in blues, yellows and oranges that echo and complement the other elements of floor, figure and table. The painting is lit from the back by a pinkish tinged plane that holds subtle traces of floral patterning. About four fifths of the painting is built of pattern; only the arms, legs and face of the child, the table and the plant pot are without decoration. The child is looking into the floor, and is simultaneously supported by, and held within, the blue and white pattern of the floor. The figure of the child is the central image of the painting, however, the narrative is emmeshed into the patterned depictions of the domestic interior. The stark way in which the curtain fabric section is placed against the patterned floor denies the suggested space of the room, compressing the depth of illusionistic space occupied by the child, and forcing the figure to sit more clearly at the front of the painting space. This pictorial device reveals rather than conceals the child, allowing that figure to be more vulnerable and less protected than the image initially suggests. Although at first glance this is a single figure painting, the viewer and potentially another person, child or adult, are behind the curtain. This absent presence provokes an underlying uncertainty about the nature of the game being played out, and the nature of the person behind the curtain. If the viewer is indeed the only one behind that curtain then there is an atmosphere of discomfort at the centre of that viewing. Gerda Roper has referred to the "dread of being found or worse, forgotten" that is an essential part of the game of Hide and Seek. In Hide and Seek in the quiet of the day there is a sense that the hidden person who is behind the curtain, beyond the painting, is observing but not necessarily seeking the child, and thus in this painting there exists the possibility of being seen but not sought.

In Hide and Seek by Moonlight, the blonde blue eyed child is half hiding and half sleeping under a small pink table on which sits a glowing golden pink vase containing large flowers, the petals of which suggest hands with pointed fingers. Behind the table is a soft plush sofa upholstered in a rich patterned fabric. The table and the sofa sit on a carpet of blue and red sunflowers which the child appears to be resting upon. The space between the sofa and the carpet is a moonscape; the night sky a deep ultramarine blue and the moon a hot alizarin crimson. The flowers appear to be seeking, reaching up towards the moon, but by contrast the child is looking straight out of the picture space. The painting of the carpet blends into the blues of the night sky. It is as if the child is laying on a large soft voluminous cushion that provides comfort and security whilst he waits to be found. The petal hands can be read as being protective of the child, but also as very slightly threatening as they appear to grasp outwards and to reach beyond the vase. The painting presents a reverie but the petal hands strike a discordant note to the overall harmony.

In Hide and Seek by Moonlight, the blonde blue eyed child is half hiding and half sleeping under a small pink table on which sits a glowing golden pink vase containing large flowers, the petals of which suggest hands with pointed fingers. Behind the table is a soft plush sofa upholstered in a rich patterned fabric. The table and the sofa sit on a carpet of blue and red sunflowers which the child appears to be resting upon. The space between the sofa and the carpet is a moonscape; the night sky a deep ultramarine blue and the moon a hot alizarin crimson. The flowers appear to be seeking, reaching up towards the moon, but by contrast the child is looking straight out of the picture space. The painting of the carpet blends into the blues of the night sky. It is as if the child is laying on a large soft voluminous cushion that provides comfort and security whilst he waits to be found. The petal hands can be read as being protective of the child, but also as very slightly threatening as they appear to grasp outwards and to reach beyond the vase. The painting presents a reverie but the petal hands strike a discordant note to the overall harmony.

In his 2013 Reith Lecture Beating the Bounds, Grayson Perry argued that it is 'a very noble thing to be decorative' as an artist. Decoration is typically described as serving to make something look more attractive or ornamental. Pattern may be used to enhance the visual attractiveness of an object or an image but pattern can be far more than a repeated decorative design, as it offers a regularity in the world, and indicates a particular way in which something is organised or happens. Pattern can communicate through intelligible form or sequence, and this is certainly true in the work of Gerda Roper. In Hide and Seek in the Quiet of the Day the majority of the painted surface is formed of patterned areas representing flat surfaces and fabrics.

Many artistic precedents exist for this but the most pertinent references for Gerda Roper's paintings are to be found in the domestic interiors of Pierre Bonnard Nude in the Bathroom (1946), Winfred Nicholson's Arab Roses (1971), and the paintings of Jean-Antoine Watteau, for example, Le Enseigne de Gersaint (1720). Her use of hot colour palettes is reminiscent of Odil Redon.

In Gerda Roper's paintings the natural world is brought into domestic spaces through the use of decoration and pattern. Patterned elements such as curtains, chairs, wallpapers, pots of flowers and lamp bases, anchor the images in specific places. Gerda Roper writes of her practice, "I am always mindful that a painting is read as much by how it is painted as what it depicts. A practice more readily understood in abstract work but also remobilised in figurative painting". This observation is particularly interesting in relation to the set of drawings and paintings that feature curtains as the main motif. Gerda Roper says of this ongoing series, "I still love the thrill of the morning light coming through a curtain, but I suspect they are the only paintings other than flowers which have no figure, no narrative in them".

However, whilst there is no figure depicted, we the viewer are present and central to enacting the narrative of paintings such as That Morning Curtain.

However, whilst there is no figure depicted, we the viewer are present and central to enacting the narrative of paintings such as That Morning Curtain.

In this painting the floral pattern of the curtain fabric, painted in a range of cadmium reds, constitutes about nine tenths of the image. Behind the red curtain sits a lace curtain, and beyond and below the curtains is a bluish area tinged with both the red of the curtain and the sunrise beyond the window. The curtains appear to be activated but a slight breeze and the handling of paint allows the whole image to gentle breathe in and out. The painting can be seen as an exquisite evocation of the experience of awakening from sleep in a bedroom filled with glowing light and the optimism of a new day, the fabric representing the bodily and the sensual. However, patterning and decoration can be used to dissemble and to conceal, to create unease as well as to comfort, and this image hints at other female experiences of closed domestic spaces and the concealment of identity emmeshed within the home.

Gerda Roper remembers The Moon Beyond the Curtain, as one of the first paintings she made when she returned to live in Wales and adjusted to life in a new house by the seafront. It is a painting about being in bed in the warmth and comfort of the home and looking out at the unrelenting sea beyond. The glow of the interior contrasts with the light of the moon and the two, the inner and the outer lights, meet at the finely drawn edge between the two forms, where they are held in visual tension between warm and cold, challenging and alluring, and comforting and safe. The painting of the curtain eloquently suggests the soft tactile qualities of draped fabric and the pleasures of bedlinen and the bedroom. The sea is represented by a flattened area and seems to tug slightly at the edge of the curtain, perhaps as a metaphor for the pull between interior and exterior worlds, and the raw realities and beauty of nature as represented by the sea, in contrast to the controlled and systematised representation of nature in the curtain. The focal point of the small full moon is at the extremity of the upper right side of the painting. The rendering of the fabric suggests a strong feminine presence especially when set against the blues of sea and sky. As in That Morning Curtain we the viewer are present within the extended frontal space of the painting, but in this work there is a suggestion of a person in the room between ourselves and the beautiful pink curtain. The person is present but invisible, sensed but not seen, hinting at the invisibility of many women who live alone and whose existence is somewhat hidden from view.

Gerda Roper's work is characterised by her use of accessible, human, and deeply absorbing imagery, her gentle humour, and intense and acute levels of observation of people, situations and encounters. Her work is distinguished by highly skilled draughtsmanship and deft paint handling, which she utilises to create paintings that allow the viewer to suspend belief and enter into other realities. This is achieved with great subtlety, and a very individual lightness of touch in the use of scale and palette. We find the paintings absorbing because the artist has so carefully observed and felt the realities of the situations and people that she depicts, and as result the experience of engaging with them is uniquely rich and rewarding.

Jill Journeaux 2020

Jill Journeaux is Professor of Fine Art in the Centre for Arts, Memory and Communities, at Coventry University. She convenes Drawing Conversations, an ongoing series of exhibitions, symposia and publications. Her art is in private and public collections in the UK, Channel Islands, the USA, France, Germany and Portugal.

www.jilljourneaux.co.uk

References

- Moll, H, and Khaluyan, A., 2016, Young children are terrible at hiding, https://theconversation.com published November 18th 2016, accessed 27/07/20.

- Roper, G., 2020, email conversation.

- Perry, G., 2013, Reith Lecture, BBC Radio 4. www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b03dsk4d, accessed 28/07/20.

Throughout her many years of devotion to the training of future generations of artists, Gerda Roper has harboured another devotion, a personal, private devotion to an art of small wonders. What are these small wonders that have so fascinated her? They are of a kind deeply rooted in the subject matter of painting: the wonder of everyday things seen afresh.

Throughout her many years of devotion to the training of future generations of artists, Gerda Roper has harboured another devotion, a personal, private devotion to an art of small wonders. What are these small wonders that have so fascinated her? They are of a kind deeply rooted in the subject matter of painting: the wonder of everyday things seen afresh.

The still life, the domestic, the everyday world of home and hearth has long been an important subject for painting. Yet the expressive properties of such genre painting were utterly transformed when the coming of photography released it from the expectation of verisimilitude. It was then that the free play with form, space and colour, the pictorial elements that are such a boon to painting’s expressive means, came to the fore. The consequences of these new possibilities have come down to us through the decades.

So, firstly, the ordinary of objects of domestic life, the ordinary rituals, pastimes and chores of everyday existence can now be depicted as imbued with the magic of daydreams, myth and the fantastical. Secondly, the rendition of space, volume and place have been released from the perceptual straitjacket of traditional perspectival means that formerly the people, objects, the components of everyday life were subjected to. Thirdly, the freedom that Gerda Roper so clearly relishes, is that colour has been released from the requirements of naturalistic description, bringing magical new possibilities to bear on the transformation of the everyday.

These three freedoms, so extensively explored in painting from Daguerre to now, during what we might call the long twentieth century, form a backdrop to Gerda Roper’s paintings, and our appreciation of them. While she employs all three, we can see that in her case colour is of particular importance, making her part of a tradition that runs deep in 20th century painting. The heightened experience of the ordinary, from the Jewish mysticism of Marc Chagall to Paul Gauguin’s impossible idyll of South Sea escape is made visible by an the gorgeous, suffocating, hallucinogenic possibilities inherent in colour. And Chagall and Gauguin are but two early examples from an enormous range of outcomes that have enjoyed the possibilities of colour released from naturalistic description. Post- Impressionists, Les Nabis, Fauvists, Expressionists and so on, down the decades, have all sought to exploit the transformative properties of colour, heightened and suffusing the pragmatic, utilitarian and subfusc with dream-world brilliance, brightness and symbolic power.

But let us not forget that for Gerda Roper there are, in a more immediate sense, her Welsh antecedents. Here we cannot fail to mention two Welsh touchstones for the elevation of small things into wonders; artists who saw the symbolic and mythic possibilities inherent in homely celebrations and rituals., recasting the poetic potential of the everyday in a way that was both Welsh and accessible to all: Dylan Thomas and David Jones. Both were extraordinary poets, one – Dylan Thomas – not a visual artist to be sure, but still a telling influence on the Welsh visual sensibility. While these two are not Gerda Roper’s only companions in the studio, they are very close to her heart. So it is that she, as any artist and academic must, draws on her antecedents, wherever her allegiances take her. Yet her paintings show with perfect clarity that the transformative deed inherent in re-imagining the everyday must be made anew, in the same magical way in which art is reborn everyday from the humdrum activities of the studio.

Nick De Ville 2021